- Home

- Larry King

Truth Be Told Page 17

Truth Be Told Read online

Page 17

I’ve always said, this ain’t brain surgery. But in one small way it is. You feel like you don’t ever want to let down the people who’ve come to see you. I remember Joe DiMaggio being asked why he hustled so much. He said, “The people who were there today may never see me again.” I know just what he meant. Whenever I look at that microphone, it reminds me: I owe them my best.

There were many surprises planned for the final show; I went in without knowing who was coming. Well, I knew that Bill Maher and Ryan Seacrest would be with me for the evening. But that was all I knew.

Many people thought I lobbied for Ryan as my replacement. That’s not true. I wasn’t involved in the process. But I’ve always said he’d have been a great choice. I don’t know if he has the background in politics, but he’s dynamic, smart, funny, and comfortable in the chair. On this one night, he had the blue cards in front of him that contained all the surprises and guided the show. So, in a way, he was in charge.

And you’ve got to hand it to Bill Maher. Right at the top he said he didn’t want it to be a funeral—and his humor made sure it wasn’t. After Governor Schwarzenegger came on to declare it Larry King Day in California, Bill kicked in with, “The proclamation was stuck in the legislature for two years.”

Then came a video clip from President Obama: “You say that all you do is ask questions, but for generations of Americans the answers to those questions have surprised us, they have informed us, and they have opened our eyes to the world beyond our living rooms. So thank you, Larry, and best of luck.”

Maher followed that with, “John Boehner is calling and he disagrees completely. He’s calling Obama a socialist for those remarks.”

Then it was old friends time—though I never think of Regis Philbin as old. He’s evergreen to me. Donald Trump appeared, Suze Orman, Dr. Phil. I’d never thought of it before that night, but you don’t see too many bald guys on television. Dr. Phil is calm, compassionate, strong—and damn good at what he does. It doesn’t matter if you’re in real estate, finance, or psychology, you don’t stay around this long without being good. There’s a lot to be said for longevity.

There was a wacky segment in which Fred Armisen of Saturday Night Live came on and impersonated me. Same glasses, same red polka-dotted tie and red suspenders. He was me interviewing me. I’m not sure how well it worked. But there were some laughs, and no show goes perfectly.

Then came the four anchors: Barbara Walters, Brian Williams, Diane Sawyer, and Katie Couric. I had no idea that Katie has been writing poetry for years. She and my producer, Wendy, wrote one that was not only touching, but had some lines that stick with me.

You made NAFTA exciting, and that’s hard to do.

And you scored Paris Hilton’s post-jail interview.

You went gaga for Gaga, Sharon Stone, Janet Jackson.

Alas, it was Brando who gave you some action.

The next surprise was Bill Clinton via satellite from Arkansas. He looked like he’d totally rebounded after his heart surgery earlier in the year. And just the week before, he’d given a press briefing for Obama at the White House. So I said, “We’re both in the Zipper Club. By the way, you looked very good in the briefing room at the White House. Did that make you yearn to return?”

Bill said no. I began to move on. I didn’t realize that there were people who didn’t understand what I meant by the Zipper Club. Apparently, some people were wondering about another sort of zipper. So Greg, in the control room, came on in my earpiece, as he’s done so many times before, to set things straight. When I explained to viewers that I was referring to the zipper scar left by surgery, Bill smiled and said, “I’m glad you clarified that.”

That’s the thing about Bill Clinton. He’s impossible to dislike. Take the person who hates Bill Clinton the most, put him in a room with him, and he’ll love him in fifteen seconds.

A camera panned the control room. For seventeen years Wendy Walker has been with me—sometimes calling me more than ten times a day. Cannon was sitting on her lap. She’ll remain as close as family.

Then there was a heartfelt moment with Anderson Cooper. Anderson is a very different broadcaster from me. It’s amazing how he does it. Not only does he put his life on the line, but he puts his thoughts on the line—like how critical he was of officials during Hurricane Katrina. You always know where he stands. And his words came straight from the heart once again.

He talked about a lunch we’d had recently—a lunch in which we’d spoken about our fathers. Anderson had also lost his father as a child, when he was ten.

He pulled out a letter that his dad had written to him before he died and read from it as the clock ticked down on my final show. It said: “We must go rejoicing in the blessings of this world, chief of which is the mystery, the magic, the majesty, and the miracle that is life.” Anderson said I had done just that—and he imagined how proud my father would be.

It’s been sixty-eight years since my father died. But I think I know what he would have felt. Nachas, it’s called in Yiddish. A pride in the happiness that you’ve helped give someone you care about. I know this feeling. I know it because I felt it a few minutes later. I felt it when my young boys came on the set with Shawn. Chance, the serious one, said he’d be happy to have me at home more. I don’t think he knows how I steeled myself so that I didn’t cry after my father’s death, but he told me it was OK to cry on the show’s final night. And then there was Cannon, the comic, who did his impression of me. First the chin in the fist, then the glance at the watch. Then, the gravelly voice: “Where’s Shawn? Get in the car! I’m too old for this. I’ve done this for fifty years!”

That was the highlight of the evening for me. And there was Shawn. It had not been an easy year for her. But there she was, made-up, beautiful, radiant—and looking forward to our future.

Tony Bennett came in right on time. From the middle of a concert, he sang “The Best Is Yet to Come.” Then Tony had his audience give me a standing ovation.

The final moments approached. I had no idea what I was going to say at the close, but then I never know what I’m going to say. The only thing I knew was I was not going to use the word goodbye. This is what came out:

“I don’t know what to say except to you, my audience, thank you. And instead of goodbye, how about so long?”

Then I watched a spotlight shine on the microphone and the entire set fade to black.

We were in a rush to get to the party at Spago. Hundreds of people were waiting. I tried zipping up my jacket, but the zipper wouldn’t catch. Cannon said, “Here, Dad, let me do it.” And he zipped it up.

Then I was coming down the red carpet and into a swirl of people all wanting to tell me something good. It’s hard to explain how that makes you feel. There was my brother, who watched it all from the beginning, and his wife, who helped nurse me through heart surgery; my older kids, Andy, Chaia, and Larry Jr.; the gang from Nate ’n Al’s. I was even happy seeing the suits from CNN. Every time I turned, I’d see Kirk Kerkorian or Jane Fonda or Jimmy Kimmel. Jimmy wanted to know if Cannon could come on his show. I was hungry and grabbed a couple of slices of Wolfgang Puck’s pizza. It was a great evening, but I have to be honest: I’d much rather have been at a party honoring someone else. With all the toasts and speeches and hugs, you know what I was thinking? I’ve got to get the kids home. They’ve got school tomorrow.

The next morning I was up at 6:15 a.m.—just like always. As soon as my eyes opened, I shot out of bed, ready to go.

It would take a while, but in time, I understood that the advice Colin Powell had given me about leaving was only half right. When the subway reaches the last stop and is getting ready to go back, it’s true that it’s time to get off that train. But as Shawn said, “That’s when it’s time to get on another train.”

13

Comedy

If I had a chance to do it all over again ...

I’d do just what I’m going to do now.

Be a stand-up comic.

There’s no more exhilarating feeling than walking out on a stage and making people laugh. It’s orgasmic. I’ve always dreamed of doing a one-man show on Broadway. Who knows? Maybe in the future it’ll be one more thing that I can’t believe ever happened to me. For now, I’m taking a comedy show on the road. A guy asked me if I’m going to wear suspenders. What did he expect? A cape and a Phantom of the Opera mask? I’m not going to reinvent myself. I’m just going to show the world another side of me.

And if there is a touch of sadness left behind by the ending of Larry King Live, this is the best way to deal with it. As the playwright Neil Simon once told me, comedy is tragedy turned inside out.

The stories I’ll tell in my comedy show will be embellished a little—but they’re all true. They come from the panicky moments and foxholes of my life. Like the time when the Mafia guy who owed me a favor asked me if there was anybody I didn’t like. Or the day before open-heart surgery when I met my surgeon for the first time and counted only nine fingers. I would definitely list the day of Moppo’s assembly as one of the five worst of my life—right up there with my father’s death and Bobby Thomson’s home run against the Dodgers. But now that day brings only smiles. Almost everything can become funny over time if you look at it the right way.

If you’ve ever seen me as a guest on late night shows you’ll have a sense of what my comedy show will be like. On Larry King Live I asked one-sentence questions. But I’m very different when I’m in the other seat. I once made Jon Stewart fall out of his chair.

My challenge is the one faced by every comic. You’re standing on that stage, and there’s no telling if the audience will laugh. As Sinatra once said to me, “What if it ain’t there? That goes through you for a minute. What if when I walk out, I don’t get that prize?”

The good news is, a lot of the material is unbombable. My stories have been refined over decades. Plus, I’m working the show out with my nephew Scott Zeiger, who produced Billy Crystal’s 700 Sundays. A long time ago, I gave Scott his start by getting him a job at Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Now he’s showing me how to put together a big-time show.

Most important of all, I’m going out there with the passion of a kid getting to live his dream. But I have one big advantage: I’m seventy-seven years old. Inside me, there’ll be a piece of all the great comics who have made me laugh since I was a boy.

A little Don Rickles. Some Mel Brooks. And a few others I’d like to nod to simply because they make me smile ...

Abbott and Costello

“Who’s on First?” may be the best comedy skit ever. I never realized that Abbott and Costello’s TV show was the model for Jerry Seinfeld’s sitcom until my final interview with Jerry.

Bud and Lou always came out in front of the curtain at the beginning of their show. Jerry ended each show doing stand-up in front of a curtain. Bud and Lou lived in an apartment house. They were always running into people and getting into hijinks. Same with Jerry, George, Kramer, and Elaine. All silly, with very little depth, but lots of laughs.

Another thing I didn’t realize until my final show with Jerry is that most comedians are left-handed. Jerry passed that on as he signed an autograph. He told me that 60 percent of comedians are lefties, as compared with 9 percent of the total population. It has something to do with the right brain being the center of creativity.

I guess I’m in the minority. I’m a righty, but I’m funny.

Groucho Marx

I would love to have met Groucho. I just barely missed him one morning years ago. He was taking out food from Nate ’n Al’s as I came through the door.

All comics want you to love them. They’re all pleading: I’ll deprecate myself. I’ll do anything. But, please laugh. All comics except Groucho. Groucho was the only great comic who never asked for your sympathy. His comedy was attitudinal. He didn’t give a damn.

“I wouldn’t want to belong to any club that would accept me as a member.”

That’s genius. That’s when you’re above it all.

Don Rickles

It was always the half-truth with Rickles—a safe attack.

He’d see Sinatra in the audience. “Frank ... Frank . . . The chambermaid, Frank? Couldn’t go an hour without it, huh, Frank?”

Joey Bishop would be laughing, and then Rickles would tag it with: “Joey, you can laugh. Frank says it’s OK.”

So, it’s risky. But is it risky? He hits, but not hard enough to hurt anybody. It’s over the line. But nobody ever comes back over the line to attack him—although Don tries to make you think retaliation is imminent.

Like the night Sidney Poitier and I were at a table at the Fontainebleau to see him.

Rickles walked onstage and saw us.

“Jeez, Larry, you’ll hang around with anybody, huh? Sidney, I don’t know what you’re doing here. No fried chicken. No watermelon.”

Sidney was laughing, but Rickles turned to the band in a panic: “Is he coming up? . . . Is he coming up? . . .”

Mel Brooks

Mel Brooks is the funniest person I’ve ever met. I’ve always loved his definition of comedy and tragedy: “Comedy is when you fall down an open manhole. Tragedy is when I cut my finger.”

I was one of the first disc jockeys to play his 2,000 Year Old Man album. You can’t tell someone what’s funny. But to me, if you don’t think the 2,000 Year Old Man is funny, there is something severely wrong with you.

Carl Reiner asked Mel, in character as the 2,000 Year Old Man, “Did you know Freud?” There are a million things Mel could have done with that. But he went with: “What a basketball player! Best basketball player in Europe!”

“Basketball?”

“You don’t know about the basketball? Your books don’t tell about basketball? Oh, I know why. He passed off. He fed the other guys. He was a point guard. He didn’t like to shoot.”

So, now, Reiner asks the logical follow-up question: “What about psychiatry?”

As if as an afterthought, Mel says, “That was good.”

“How about Shakespeare? Did you know Shakespeare?”

“Of course I knew Shakespeare.”

“What a great writer!”

“Hold it! Stop! Whoops! P looked like an R. S looked like an F. Failed penmanship three straight years!”

That’s lasting. That doesn’t go away. It’s like The Honeymooners . It holds up. The great ones are never dated.

Comedy is based on the element of surprise. It can also diffuse the tensest of situations. Mel was a master at both because he’s so quick. On opening night of The Producers, an angry guy from the audience came running over to him at intermission. “I served in World War II,” he said. “You are making fun of that war! You’re making Hitler into a comic. You are humiliating everyone who served! I’ve never been so embarrassed. I’m ashamed of this show.”

Mel says, “You were in World War II?”

The guy says, “Yeah.”

Mel says, “So was I. Where were you? I didn’t see ya . . .”

Mel could also set you up. One time, he was booked to fly to Washington for my all-night radio show. “Can you meet me at the airport?” he asked. “I can get a limo, I know, but it’ll be nice if you drive out.”

So I went out to Dulles. I waited. He walked off the plane with a crowd behind him. As soon as he saw me, he turned to everybody and yelled, “Did I tell ya? When I do a show, the host comes to the airport!”

Lenny Bruce

Every comedian you see now who uses profanity owes Lenny a debt. If there had been no Lenny Bruce, there would have been no Richard Pryor. No Richard Pryor, no Eddie Murphy. No Eddie Murphy, no Chris Rock. Chris Rock gets paid for doing the same thing that Lenny Bruce got arrested for doing.

Lenny was the first one to curse onstage. He changed the culture. But he didn’t curse just to curse. There was a point behind it. He used words to make you think.

He’d say: “Fuck is colloquial for intercourse. So, I don’t get mad if so

mebody says ‘Fuck you, Lenny!’ And if I get mad at someone, I tell him, ‘Unfuck you, forever!’”

Although he was infamous at the time for his language, I think he was arrested more for the way he spoke about religion. But it didn’t matter how much he got fined or arrested. He refused to change. Bob Hope would go see him and say, “Lenny, lighten it up a little bit and you’ll get on every television show in the world.” But Lenny wouldn’t go on Ed Sullivan. It was frustrating. It was easy to want him to be what he refused to be. He was a great mimic. He did a great Chaplin. He just wouldn’t cop out. He thought it was insane to be upset over language.

Once while performing in San Francisco, Lenny used the word cocksucker onstage. The police hauled him away and drove him to night court.

In the car, the cop driving said, “You’re a funny guy. A real funny guy. Why do you have to say words like that?”

Lenny says, “It’s just a word. Ever had your cock sucked?”

The cop sitting with the driver said, “Ah, the wife don’t like it.”

The driver said, “Your wife don’t like that? It’s the best thing.”

“Oh, my wife ... How do I get my wife to do it?”

Now Lenny’s giving him advice. He tells him to take a banana to bed.

So all the way down to court they’re talking about blow jobs. They get to the court. Reporters have followed them. The court is packed.

Next case: Lenny Bruce.

The charge: Lewd and lascivious language in a public place.

The judge says, “What did he say?”

The cop says, “I’m sorry. I can’t repeat it in an open court.”

Lenny, of course, was his own best lawyer even though he had an attorney. He says, “Your honor, you can’t rule unless he repeats it.”

The judge says, “He’s right, you’ve got to repeat it.”

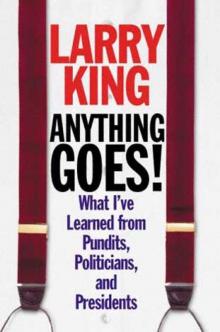

Anything Goes

Anything Goes Truth Be Told

Truth Be Told