- Home

- Larry King

Truth Be Told

Truth Be Told Read online

Table of Contents

ALSO BY LARRY KING

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1 - Time

Chapter 2 - Leaving

Chapter 3 - Riches

Portrait of My Dad

Chapter 4 - Music

America the Beautiful

Day-O

Malice in Wonderland

Hello, Dolly!

Ma Cherie Amour

I Walk the Line

Best That You Can Do

God Bless America

The Christmas Song (Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire)

Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate the Positive

Misty

Yesterday

I Write the Songs

Take the “A” Train

Oh, What a Beautiful Morning

I Will Always Love You

MacArthur Park

Remember

Bat out of Hell

Silent Night

A-Tisket, A-Tasket

The Kid from Red Bank

This Land Is Your Land

Begin the Beguine

The Way We Were

Light My Fire

Chances Are

I Left My Heart in San Francisco

Rhythm Is Gonna Get You

New York State of Mind

Honey in the Horn

Way Down Yonder in New Orleans

Graceland

Blue Skies

Birth of the Blues

School’s Out for Summer

The Lawrence Welk Show Theme

Escapade

On the Street Where You Live

Unforgettable

My Heart Will Go On

La Vida Loca

Born in the USA

Hero

Poker Face

Coca-Cola Cowboy

Gone Too Soon

Melancholy Baby

Candle in the Wind

Long Day’s Journey

Don’t Be Cruel

Imagine

Hey Jude

She’s So Fine

Something in the Way She Moves

Thriller

Satisfaction

Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer

Respect

Cardiac Foundation Gala

Shameless

I Dreamed a Dream

Volare

Put Your Dreams Away (For Another Day)

That’s Life

Baby

The Way You Look Tonight

Chapter 5 - Movies

Chapter 6 - Crime

Chapter 7 - Broadcasting

Chapter 8 - Politics

Chapter 9 - The Middle East

Chapter 10 - Getting and Giving

Ryan Seacrest

Chapter 11 - The Replacement

Chapter 12 - The Finale

Chapter 13 - Comedy

Abbott and Costello

Groucho Marx

Don Rickles

Mel Brooks

Lenny Bruce

Joan Rivers

George Carlin

Henny Youngman

Milton Berle

David Letterman

Jay Leno

Conan O’Brien

Jimmy Kimmel

Jimmy Fallon

Lewis Black

Woody Allen

Larry David

Bill Maher

Stephen Colbert

Jackie Gleason

Kathy Griffin

Craig Ferguson

Bob Hope

Colin Powell

Robin Williams

Shecky Greene

Steven Wright

Mark Russell

Jon Stewart

George Burns

Saturday Night Live

Index

Copyright Page

ALSO BY LARRY KING

My Remarkable Journey

The People’s Princess

My Dad and Me

Taking on Heart Disease

Remember Me When I’m Gone

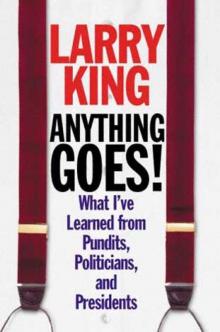

Anything Goes!

Powerful Prayers

Future Talk

How to Talk to Anyone, Anytime, Anywhere

The Best of Larry King Live

When You’re from Brooklyn, Everything Else Is Tokyo

On the Line

Tell Me More

Tell It to the King

Larry King

This book is dedicated to Hunter Waters.

Hunter was a Larry King Live producer who passed away with esophageal cancer early this year at the age of thirty-two.

I remain amazed by people of faith who can explain the passing of such a young, vital person. It always made me happy to see his smiling face. I always loved hearing the sound of his voice.

Rest well.

1

Time

I’ve never thought much about time, because I’ve always been too busy looking at my watch.

That sounds like something Yogi Berra might say. But it’s true. You can’t be a broadcaster without being extremely conscious of the clock. I’m never late. I remember a time after I had heart surgery. I was at the La Costa Resort, waiting for my surgeon to meet me so we could head to the airport. I said, “Jeez, where is he?” Somebody who knew him said, “He can be late. He’s a surgeon. Surgery doesn’t start without him.”

A broadcaster cannot be late. Well, he can. But he’ll be fired. For fifty-three years, my day has been planned around six o’clocks and nine o’clocks. It’s hard to explain how conscious of the clock that makes you. I can only give you a sense.

Not only are you always conscious of the hour when you’re in broadcasting, but you also have a heightened awareness of seconds. When you’ve repeatedly got to slide into a commercial break, you understand exactly how long five seconds lasts.

I used to have a cheap little clock on the set of Larry King Live. Every time Jerry Seinfeld came on as a guest he’d swipe it. It wasn’t a case of: The show’s over, here’s your clock. He’d never give it back. I’d have to go to Radio Shack and buy another.

“Jerry,” I finally said—after he took it for the third time. “Give the clock back.”

“You don’t need it,” he said. “You’ve got a clock in your head.”

He was right. But the strange thing about the clock in my head is that it always seems to be in the future. This is how it feels: Just say there’s a miracle and I landed an interview with God on Monday night. It’d be on the front page of every newspaper: LARRY KING TO INTERVIEW GOD MONDAY. You know what I’d be thinking? What am I going to be doing on Wednesday night?

For fifty-three years, that’s the way my mind has worked: thinking about what’s next and constantly checking my watch to make sure I’m on time for it. But that’s very different from stopping to think about time and the meaning of its passing.

As my CNN show wound down the last two weeks of its twenty-five-year run, a moment came that made me stop to reflect. During the final minute of a satellite interview with Vladimir Putin, the Russian prime minister invited me to Moscow. Then, through his interpreter, he turned the tables on me.

“Can I ask you one question?”

“Sure.”

“In U.S. mass media,” he said, “there are many talented and interesting people. But, still, there is just one king there. I don’t ask why he is leaving. But, still, what do you think? We have a right to cry out: Long live the King! When will there be another man in the world as popular as you happen to be?”

I’ve never taken compliments well, and my head dipped. It’s OK in broadcasting to look down at your notes for an instant. But your eyes can’t become glued to your desk. My head just wouldn’t come up. I doubt many broadcasters have been faced with a similar situation. It wasn

’t a mistake. A reaction isn’t a mistake. I was humbled.

For the first time since May 1, 1957, I was speechless. That moment with Putin connected me to my first moment on the air.

As I lowered the music to my theme song in the control booth of a tiny radio station in Miami Beach, my mouth felt like cotton. I couldn’t introduce myself. I opened my mouth, but no words came out. WAHR listeners must have wondered what the hell was going on when I took up the theme song again and lowered it once more. Again, no words came out. Maybe the audience could hear the pounding of my heart—but that was about it. I took up the theme song again, then brought it down for the third time. Nothing. That’s when the station manager kicked open the control room door and screamed: “This is a communications business!”

It was as if he grabbed me by the shoulders and shook the words out of me. I told the microphone how all my life I’d dreamed of being a broadcaster. I told it how nervous I was. I told it how the station manager had just changed my name a few minutes earlier and then kicked open the door. I let myself be me, and the words started flowing.

So my career had started with an awkward moment of speechlessness. I couldn’t believe I was actually on the air. And now my television show was approaching an end with another speechless moment. The prime minister of Russia has just called me a king.

The same lesson I learned on my first day guided me through the awkwardness fifty-three years later: There’s no trick to being yourself.

My head came up to look at Putin in the monitor. My words were not memorable, but they were sincere.

“Thank you. Thank you,” I told him. “I have no answer to that.”

In so many ways, the end has brought me back to the beginning. The moment with Putin makes me look back on everything that’s happened since my mother came to America by boat from the tsar’s Russia. I can picture my mother. If I close my eyes, I can even hear her voice: “Again, you’re unemployed?”

She had a great sense of humor, Jenny Zeiger. The classic Jewish mother. Truth is, only my mother would have believed that a kid like me, who never went to college, could have had such success. The more I look back, the more unbelievable it becomes. There have been so many twists and turns.

I think of my earliest memories of the Russians. As a boy I rooted for them when I studied World War II maps in the newspapers. They were fighting the Germans on the second front.

Everyone I knew loved Joe Stalin. Papa Joe, we called him. By the time I got my first teenage kiss, we hated him. Stalin had seized the Eastern bloc.

There was panic in America the year I started in radio. Sputnik had been launched. We were no longer in the lead. The Soviets could look down on us. I was a married man with a young son when I saw tanks roll down the streets of Miami during the Cuban missile crisis.

Humor helps after moments like that. The comedian Mort Sahl did a funny bit on how things change: An American soldier gets knocked unconscious during World War II and doesn’t wake up until more than fifteen years later.

“Get me my gun!” he says. “Get me my gun! I’m gonna go kill those Germans!”

“No, no,” the doctors try to calm him, “the Germans are our friends.”

“Are you crazy?” the soldier says, “We’ve got to help the Russians get the Germans.”

“No, no, no. World War II ended years ago. The Russians are our enemies.”

“I’ll tell you what then,” the soldier says. “Get me my gun so I can help the Chinese wipe out the Japs.”

“No, no, no, no. The Japanese are now our friends. The Communist Chinese are our enemies.”

“What a crazy world.” The soldier shakes his head. “I’d better rest. I think I’ll take a vacation. Maybe a couple of weeks in Cuba.”

By the time the Vietnam War started, I was interviewing everyone from generals to Soviet defectors on local radio and television. I was Mr. Miami. We were told the war would stop the domino spread of Communism. Not long after we figured out our mistake, the Soviets made one of their own and invaded Afghanistan. By then, I was on all night, coast to coast. President Carter came on my Mutual Broadcasting radio show to explain the U.S. boycott of the Moscow Olympics.

I couldn’t even get CNN on my television in Washington when Ted Turner started it. Ted didn’t see the satellite as an enemy. One of the few rules he had when I joined CNN in 1985 was that we couldn’t say the word foreign. Borders were crazy to him. He wanted to use satellites to bring people together.

By the time the Berlin Wall came down, the backdrop of my show was known around the world. Mikhail Gorbachev came to meet me for lunch wearing suspenders. Boris Yeltsin watched me announce that OJ was heading down the freeway in the white Bronco. When he arrived in the U.S. for a presidential conference, the first question Yeltsin whispered into President Clinton’s ear was: “Did he do it?”

I think back to my mother and all those Jews who left the pogroms and Russia at the turn of the twentieth century. And I think of the irony of Putin telling me in our first meeting that his favorite place in the world to visit is Jerusalem.

How could it be that so much time has passed? Seems like I was just running down the streets of Bensonhurst with my friend Herbie to celebrate V-E Day. Suddenly, I’m celebrating my show’s twenty-fifth anniversary? Then I’m announcing that my show is going to end? When I did, the most popular sports star in Washington, D.C., was the Russian hockey player Alexander Ovechkin. And Putin called to ask if he could make a final visit before I signed off. Maybe this is what Ted Turner had hoped for when he started the network.

Yes, we have come full circle. Once again, we can be friendly with the Russians. Everything changes, and everything stays the same. Again, you’re unemployed?

Why is the world like this? I have no idea—only another good joke that confirms it.

A guy living in the Bronx takes his shoes in for repair. It’s December 6, 1941. The next day, the Japanese bomb Pearl Harbor, and he enlists.

He goes overseas. He fights the war, meets a Japanese girl, marries her. He goes into business, lives in Tokyo for twenty-five years. One day he comes back to the United States for a business meeting. He’s going through an old wallet and finds a ticket stub for that old pair of shoes. It’s marked December 6, 1941.

He wonders if the shoe store is still there. So he asks his limo driver to take him up to the Bronx.

There it is! John’s Shoe Repair.

“I’m gonna go in with the ticket,” the guy tells the driver, “just to see what happens.”

He walks in. It’s the same repairman!

The guy hands John the repairman the ticket. John the repairman turns and shuffles to the back.

A minute later he returns to the counter and says, “They’ll be ready next Tuesday.”

2

Leaving

I’m not sure which comes first—acceptance or belief. When you first realize you’re about to lose something that’s a part of you, it’s hard to accept. But even when you start to accept the loss, it’s still hard to believe.

I knew my show had only a few months remaining when I sat down last September to interview the Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad for the third time. Yet as our final session ended, the words that left my mouth were: “We’ll pick this up next year . . .”

You don’t stop to think it’s the last time you might be interviewing President George Bush 41 when he lifts himself out of a wheelchair to greet you. His leg was shaking from a variation of Parkinson’s disease. He was eighty-six years old. What you do is talk about his plans to go skydiving.

Maybe my feelings about leaving can be traced back to my first memory of it—when my father left me. There was no warning. I was nine years old, walking home from the library carrying an armful of books. Three police cars were in front of my apartment. I started running up the steps when I heard my mother’s screams. A cop came down the staircase straight for me. He picked me up and the books under my arm went flying. The cop put me in a police car a

nd told me that my father had died of a heart attack.

I was bewildered at first. But then another emotion set in. I refused to cry. I didn’t go to the funeral. I stayed home and bounced a spaldeen—the Spalding rubber ball we used to play stickball with—off the front stoop. Years later, when I mentioned to a psychologist how I had purposely recited prayers in synagogue in a way to provoke pity, he suggested that it might have been because I was angry—angry that my father had left me.

Of course, I now understand that it wasn’t my father’s fault. He certainly didn’t want to leave me. But the day he left probably had more impact on my life than any other.

It may have seemed abrupt when I announced on my show in late June that I was leaving. But it was a process of evolution on my end. Looking back, there were several moments that foretold the change.

At the end of February, I got a call from my producer, Wendy Walker, and her top aide, Allison Marsh. They were elated. They’d just landed an interview with the head of the Toyota Motor Corporation, Akio Toyoda. There was no bigger story in the news at the time. Toyoda was testifying before Congress after the recent surge of accidents and deaths caused by unintended acceleration stemming from defective parts. “It’ll be his only interview,” Wendy said. “He doesn’t want to be interviewed by anyone else.”

I should have been happy. I’d been asking for a show on this topic for weeks. Not only were Wendy and the staff delivering—they were doing so big time. It doesn’t get any better than booking the guy who runs the company. But there were a couple of catches. Akio Toyoda wanted to do the interview face-to-face. And since he was testifying in Washington, that meant I had to get on a plane in L.A. the following morning to get there on time.

CNN flies me private, so the plane was no problem. But there were personal issues. Not many people were aware, but I was fighting off prostate cancer at that point. I’d also had a stent placed in one of my arteries to open up a blockage. Doctors had advised me to take it easy and avoid stress. But that seemed almost impossible. I was going through a rough patch with my wife, and there was tension at home that we were trying to work out. Shawn has a history of migraine headaches and was not feeling well on the day Wendy’s call came. I didn’t want to leave her. Plus, I’d be flying off, coming right back, then flying to Washington again a few days later for my cardiac foundation fund-raiser. Something inside told me it was all too much.

Anything Goes

Anything Goes Truth Be Told

Truth Be Told