- Home

- Larry King

Truth Be Told Page 2

Truth Be Told Read online

Page 2

“You can stay in Washington and do the show there until the fund-raiser,” Wendy suggested. Wendy was going to take care of everything. But that would mean waiting around and being away from Shawn and my two young boys for a few days. I didn’t want that, either.

“Akio Toyoda is going to be testifying before Congress all day,” I told Wendy. “It’s all going to be taped and he’s going to be on every news channel. It’s not like people aren’t going to see him answering questions. I don’t think I need to go.”

Wendy must have been stunned. She’d been producing my show for seventeen years. I’d never turned down an interview of this magnitude before. Apart from my heart problems, I’d never called in sick. From the moment I got my first job as a deejay in Miami Beach, everyone at the station knew that if they needed to take a shift off, all they had to do was call Larry. Larry would fill in. I could never get enough of the microphone. In my free time during those early days I had a second job announcing at the dog track. Then I took on a newspaper column and a local television show. On top of that, I’d speak for pleasure to audiences at the Rotary Club or Knights of Columbus. As the years passed, I took on even more. Back in the mid-’80s, I’d finish my CNN show in Washington, drive to Virginia to do my all-night talk-radio show on the Mutual network, get some sleep, then write a column for USA Today during the day—and then help raise money for my cardiac foundation to get heart operations for people who couldn’t afford them. I was always prepared to work. Since the day I went on the air, I’ve never gotten drunk. I worked fifty-three straight days after 9/11. I often went to the studio to tape shows on Saturdays and Sundays. Shawn always wondered why we could never just get in a car and drive up the coast for a week. It seemed like a nice idea. I’d never say no. But we’d never make the trip. I guess the truth is that there was no microphone in the car. I think it was Woody Allen who said that 80 percent of life is showing up. Whenever CNN needed me, I was always there.

On top of that, I hardly ever say no to anyone. On one level, the absence of negativity is probably a reason why guests feel safe around me. That’s why they’re comfortable enough to open up. But never saying no can also be a huge fault. Ten people can ask me to do a favor at the same time on the same day, and I’ll agree to all ten requests. I just don’t want to let anybody down. Naturally, that’s caused me to let down the people I didn’t want to let down in the first place, and has gotten me into trouble over the years. But I just don’t have it in me to deny anyone anything. Fifty-year-old women I’ve never met approach me at breakfast with modeling portfolios and ask if I can help them get a job in fashion. Yoga instructors show up with stretch mats and ask me to speak at their classes. Men with stashes of foreign bonds that for some reason they can’t cash ask me if I know people who can help. Why me? I’m always asking as I step out after breakfast at Nate ’n Al’s deli. But I know why. It’s because I can’t say no. That’s why my friend Sid Young sits next to me at breakfast. He says no. Sid, and my lawyers.

Suddenly, I’m saying no to an interview that Barbara Walters and Oprah Winfrey would like to have? After my staff worked overtime to pull it off? At a time when the network’s ratings were falling behind Fox and MSNBC, and negotiations were about to begin on my next contract?

I went to dinner with some friends that night but didn’t feel like eating. After a while, I wanted to throw up. I left early, went home, but couldn’t sleep. I tried to do a little reading, and finally dozed off. When I woke up it was just after midnight.

Yeah, I thought, Akio Toyoda is going to be testifying all day. Yeah, he’s going to be all over the news. But I might get more out of him. A senator only cares about how the hearing affects American car owners. He has an agenda. I don’t. I’d ask questions a senator wouldn’t consider. “Your grandfather started the company. What do all these troubles mean for you when you are in front of your friends?” His answer to this question is going to be very different from the responses that everyone will see on clips from the hearing. There are interesting things that can come out of this interview, I thought, and the best way to get those answers is face-to-face.

I went to the bedroom and looked at Shawn. She was sleeping peacefully. She seemed to be feeling better. Now my mind was really starting to fly. I could take the kids to school. Then, if I flew out at ten in the morning, I’d get to Washington around five thirty in the afternoon. I could do the show, jump back on a plane to L.A. and be home by 1:30 a.m. That way I could take the boys to school the next morning.

What was I thinking? This is a piece of cake. I couldn’t get back to sleep. So I called Wendy. It was 2:26 a.m.

“Hello! Wendy, it’s Larry!”

“Larry ...”

“Listen, if you can reach the Toyota people, tell them I’ll do it.”

We talked some more and then I got a few hours’ sleep. When I awoke and opened the New York Times it said: Snow possible in Washington. I didn’t care. I got some chewing gum for the flight. I was all set. Then I looked at my phone and saw a message to call Wendy.

The heart physician Dean Ornish had told her sometime before that I needed to avoid stress. She didn’t want to put any more on me. She said she’d try to make the interview happen by satellite—and she did. It worked out well, got big play, and everybody was happy. But looking back, I realize: For the first time, I’d said no.

The tension in my marriage kept building. I’ll get into this later on. I definitely want to clear up some misconceptions. But for now, I want to focus on how I came to leave my show and the ups and downs that came with it. So I’ll stick to the basics.

On the morning after opening day at Dodger Stadium, we got into a loud argument outside the house. I had made a mistake, and Shawn found out about it. The mistake—whether big or small—is nobody’s business. It’s between Shawn and me. I just wanted to move past it and get on with our lives. That’s how I deal with mistakes. My friend Sid was with me. I got so upset that I just wanted to get away. We weren’t exactly in Tiger Woods territory, but in driving off I nearly ran over Sid’s toe.

It’s impossible to know how Shawn felt. I felt like I was going to have a heart attack. We both filed for divorce. But there was no sense of relief. It was a miserable day. I was exhausted and didn’t know how I could do the show. Willie Nelson was the scheduled guest. He has a great line about divorce: “It costs so much because it’s worth it.” But it wasn’t amusing that day. I felt hollow as I went to the studio. Then the lights came on. It always amazes me what happens when the camera starts rolling. No matter how low or tired I feel, I shoot right up. I have no idea where this energy comes from. But there’s nothing in the world like it. Willie and I had a great hour. We sang “Blue Skies.” Shawn had recorded with Willie, and—shows you where my mind was—we talked about the two of them singing together in the future as if the divorce filings had never happened.

That night was one of the worst of my life.

I was in a hotel room only a couple of miles away from my home but it felt like I’d abandoned my sons. Chance had just turned eleven. Cannon was nine—the same age I was when my father died. Garth Brooks says that every curse is a blessing and every blessing’s a curse. That night, I think both Shawn and I understood exactly what he meant. It was a sleepless night that didn’t seem to end. But I think it made us both realize that we didn’t want to leave our kids. We didn’t want to leave our home. And we didn’t want to leave each other. I just wanted the funny, smart, and beautiful woman I married twelve years before to reappear and the arguments to stop.

Millions of couples in America have gone through the same process and emotions. But getting things back together is not easy when you’re on worldwide television and you’ve been married seven times before to six other women. That last fact alone gives late-night comics an irresistible punch line. Look, I’m not going to deny that I’ve made some mistakes along the way. But Shawn and I had been married for twelve years. That ain’t small potatoes. I have a good family. Som

ehow facts like that get lost when a celebrity marriage has trouble. The simplest act—like coming together to watch our sons play a Little League baseball game—became surreal. One night shortly after the divorce filing, there were at least sixty paparazzi snapping away at my bewildered kids as we tried to walk through the darkness to our cars. Shawn’s mother got knocked over. Cannon started crying. Shawn put Cannon on her back to protect him, threw a jacket over his head and ran down a hill with cameras flashing all around them. If I had known this was going to happen, would I ever have entered the lawyer’s office?

It took us a while to rescind the divorce papers and work things out. In the meantime, a bad vibe circulated. There’s a line between mean and funny. It felt like many of the late-night jokes crossed to the wrong side. The tabloids and Internet sites had a field day. The problem with the tabloid attention was that it set another dynamic in motion. The mainstream press started to examine CNN’s declining ratings. I was a symbol for the network, and the writers were beginning to wonder if time had begun to pass me by. It’s only natural for your staff to fight back to improve the ratings. The easiest way to do that is to book tabloid-style stories. If I disliked tabloid shows in the first place, imagine how I felt doing them when my own marriage had become one. The situation might have continued spiraling downhill if not for one saving grace: The twenty-fifth anniversary of my show was approaching.

President Obama, Lady Gaga, LeBron James, and Bill Gates were lined up as guests back to back. Another show was assembled to look at the best moments over a quarter century. It was an amazing week, and it changed the energy and the conversation. Flying back home from the White House I was on a high. That’s when everything seemed to come into focus.

In a single week, I’d sat down with the president of the United States, the hottest stars in music and sports, and a billionaire who was changing the world through philanthropy. Was it ever going to get any better that that? Or was I looking at a future of shows with fifteen reporters and analysts who’d never met Sandra Bullock all talking about her marital problems in order to prop up the ratings?

It was a year before my contract was up—the time we traditionally start working out a new one. I sometimes wonder what would have happened if Ted Turner were still running the network. Ted hired me in less than twenty-four hours, and I’m sure the meeting would have been completely different. He’s an extremely loyal guy and he would have figured out some way—any way—to keep me in front of the microphone. Negotiations were always swift and ended in three-, four-, or five-year contracts. But the Ted Turner who hired me back in 1985 had the only cable news game around. The network’s execs twenty-five years later—Jim Walton, Phil Kent, and Jon Klein—were competing in a different world.

If I had to compare myself to a ballplayer as I entered the meeting, I’d identify myself with the New York Yankees shortstop Derek Jeter. I was getting older. I hadn’t had my best year. But there were some high moments. I was associated with the network the way Jeter is with Yankee pinstripes. The backdrop to my show is one of the most recognizable images in the world. Attendance might have been down, but CNN was making a nice profit—just like the Yanks. And some of the reasons for the decline in my show’s ratings were not my own. The show leading in to mine was having a difficult time and the host ended up leaving in the middle of the year. It’s no different from baseball: If the player batting before you is hitting .350, you’re going to see better pitches and have a higher average. I didn’t have the benefit of a large audience rolling into my show. This may be a stretch, but to continue the analogy, CNN was asking me to sacrifice my numbers by moving a base runner along. Joy Behar started out as a guest on my show, then guest hosted. She’s funny, got a great spirit, and she was given her own show on CNN Headline News in my time slot, nine o’clock. I get it. The idea is to bring in as many viewers as possible and make the most money for the network. That’s corporate America. The guys at Pontiac try to beat the brains out of the guys from Buick even though they both work for General Motors. Believe me, nobody was happier than me to see Joy’s mounting success. But fair is fair. I’m sure that on some nights viewers were curious about Joy and her guests and clicked the remote to her show. My own network was cutting into my ratings and then wondering why they were falling.

The bottom line is, just as I’m sure Jeter wants to play for as long as he can with the Yankees, I wanted to stay with CNN. Over and over, the execs had told me, “You’re here as long as you like.” I figured I would be. My thoughts going into the meeting were simple. Maybe we can just lighten the workload a little and tone down the tabloid stuff.

The execs at CNN are very much in the position of baseball executives. They have to compete on the field and simultaneously prepare for the future. If they don’t, they fail. Fail, and they get fired. So they have to protect themselves in a way that Ted Turner didn’t. Ted was the owner. Ted cared more about money than ratings. If you said to Ted, which do you prefer, to be first in the ratings and make 1 million or be third in the ratings and make $1.3 million? He’d say, give me the $1.3 million. CNN was doing very well. It was making more money than Fox. But it was easy to see management’s point of view. Broadcasting is not the same as it was in 1993 when 16 million people tuned in to the debate on my show between Vice President Al Gore and Ross Perot. The market has been fractured and tastes have changed. People are tuning in to cable news now not so much to get educated as to be entertained and have their own political opinions reinforced. A host like Bill O’Reilly uses his guests as props. One of the Nate ’n Al’s breakfast gang once said that if Glenn Beck could get Kleenex as a sponsor he’d weep on cue four times a day. CNN’s execs were competing in that world—and their prime-time guy was about to turn seventy-seven. Their prime-time guy would never beat down his guests. Their prime-time guy didn’t want to do the tabloid stuff.

They made their proposal. It was not for the multi-year contract I was expecting. Maybe I felt something that every player who’s been on the all-star team feels when the days of the long-term contracts end. Whatever happened to “You’re here as long as you like”? Maybe broadcasting had changed, but there were still a lot of people who wanted to see me do what I do. I know this because I hear from them every day. They prefer to see people they’re curious about candidly talking about their lives. They aren’t interested in the shock and gossip tabloid stuff. But hey, the bottom line is, if the host ain’t happy, we’re all just spinning our wheels.

There was some back-and-forth between CNN, my agency, and my lawyer, Bert Fields. Bert came to me and said, How about this? You’ll work a few more months until they get a replacement. You’ll be paid the full final year of your contract. And then, for three years after that, you do a series of four specials a year on mutually agreeable subjects.

The specials would be for less money than I was making at the time, but it was still good money, and I’d be a free man. I could work for other networks. I could do commercials. I could do the one-man comedy show onstage that I’d always wanted to do. I would no longer have to clear anything with CNN. Their only condition was that during the period of the agreement I couldn’t work for MSNBC or Fox.

It sounded good. I’d be able to spend more time with Shawn and the kids, I’d still be with CNN, plus I could do things on my bucket list. At the same time, it sounded sad. Not only would I be leaving the show, but forty people I really cared about would be losing their jobs.

I thought it over. It felt like the right way to go. Wendy got a hold of the comedian Bill Maher. He moved an engagement so he could be my guest the night I announced my decision to leave. The toughest part was saying goodbye to the staff. They were losing their jobs and they were crying for me. It was good to have Bill as a guest. Humor always helps.

Soon after he heard the news, Colin Powell called to wish me well. He passed on a piece of advice that had been passed on to him by a brigadier general: “When the subway gets to the last stop and is getting ready to go back, it’

s time to get off the train.” He said I got off at the right time.

The calls and good wishes from so many friends were incredibly uplifting. For months the press had been wondering: Has time passed him by? Now the response was: Oh, no! What are we losing? But it felt awkward when people started to congratulate me on my retirement. Retirement? Who said I was retiring? Retiring to what? I started to wonder what I was going to do when the show did end. I’m a creature of routine. What happens when there’s no Wednesday night? There has to be a Wednesday night, because I’m a productive fellow. Thinking about no Wednesday night started to make me depressed. A psychologist told me that I was sitting shiva for my show. Shiva is the traditional ritual in Judaism used to comfort relatives of the deceased. The show was not dead yet. But it felt like the family was gathering.

A few weeks after the announcement, something happened that I’d never seen before. A free-agent basketball star got a one-hour prime-time special on ESPN to announce whether he would stay with his team or leave for another city. I wasn’t able to watch LeBron James’s decision live. My own show was on up against it. But I did get to see it on tape. It was a lesson in how not to leave.

I was surprised because of what I’d seen in LeBron a few weeks before when I spent the day at his home in Akron. I found him to be humble, very bright, and a good conversationalist. There was a moment that really stood out. We were walking to the basketball court he has outside his house to shoot some hoops when he told his son, “Larry King is in my house. If you would have told me that Larry King would be in my house when I was a kid, I never would have believed it.” He wasn’t buttering me up. He said it after the interview—not before. It was sincere and respectful. Which was the opposite of the way he came off when he announced his decision on live television.

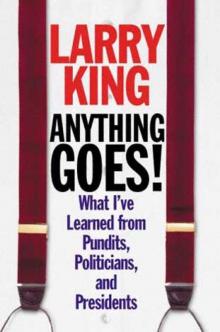

Anything Goes

Anything Goes Truth Be Told

Truth Be Told